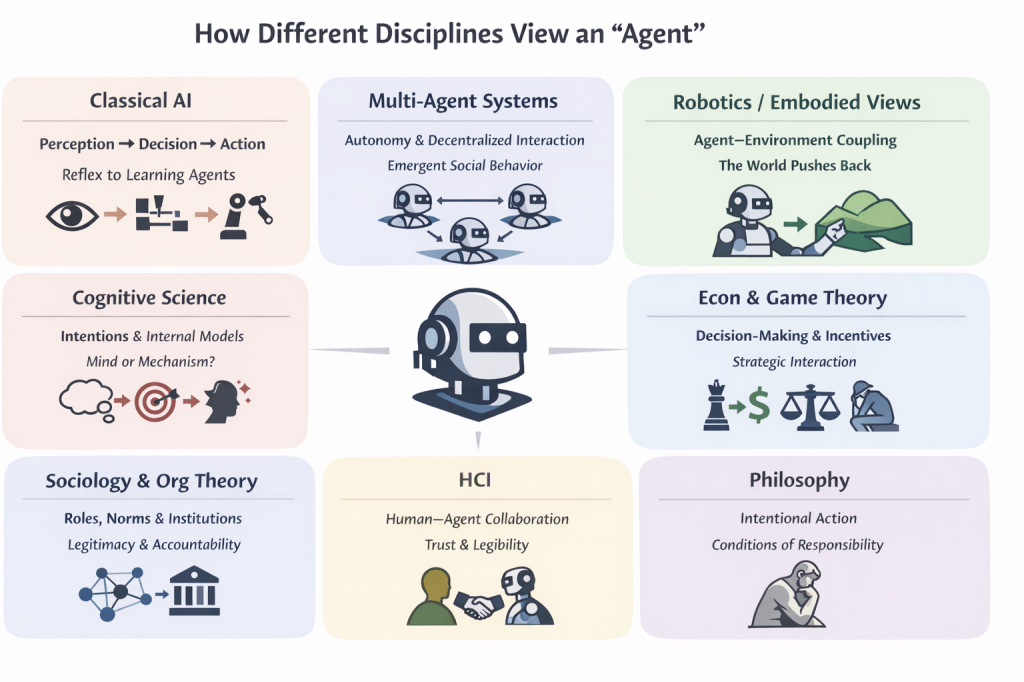

In the first post, I suggested that we might benefit from a clearer way to think about AI agents — something I called agentics. Before we can talk about a science of agents, though, we need to confront an awkward fact:

Different fields mean different things when they say “agent.”

So in this post, I’ll take a brief tour of how major fields define agents — and what that implies for agentics.

The Classical AI View: Agents as Rational Actors

A foundational definition comes from Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig, in Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach:

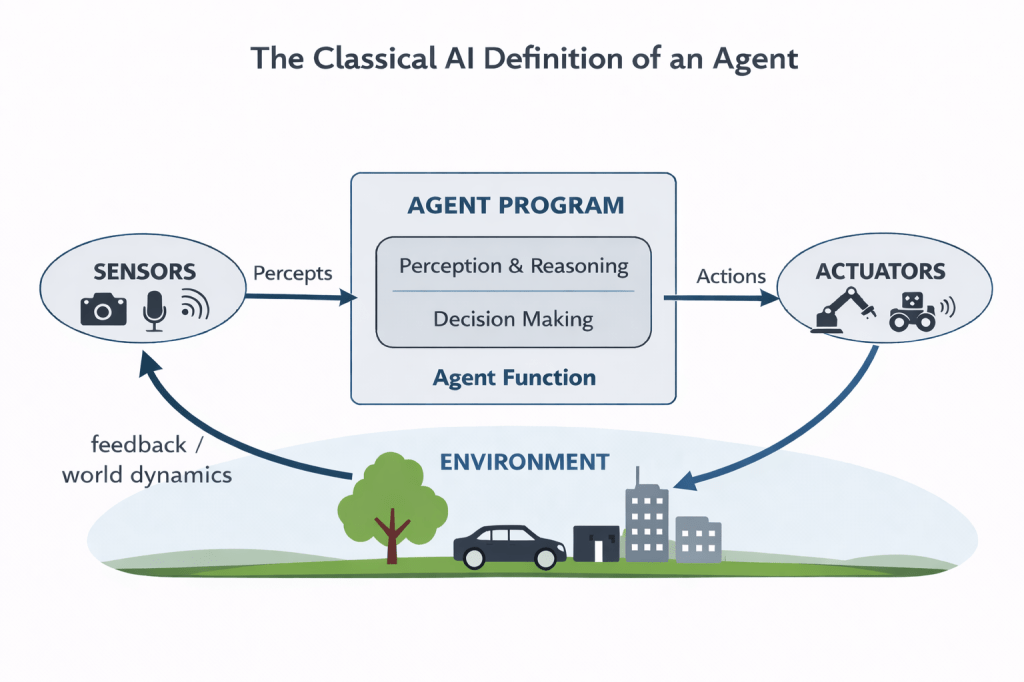

“An agent is anything that can be viewed as perceiving its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through actuators.”¹

Here, the emphasis is on the perception → decision → action loop. The authors describe an agent function, instantiated by an agent program, that maps an agent’s percept history (inputs from sensors) to actions (outputs to actuators). The agent program is what determines the agent’s behavior, and intelligence is evaluated in terms of how rationally the agent selects actions to maximize a performance measure.

Russell and Norvig distinguish several canonical agent architectures based on how the agent function is implemented:

Simple Reflex Agents

Act only on the current percept, using condition–action rules, without reference to percept history.

Model-Based Reflex Agents

Maintain an internal state derived from percept history, allowing them to function in partially observable environments.

Goal-Based Agents

Select actions by considering future consequences in order to achieve explicit goal states.

Utility-Based Agents

Select actions to maximize a utility function, allowing trade-offs among competing goals or uncertain outcomes.

Learning Agents

Augment any of the above architectures with mechanisms that improve performance over time through experience.

This framework helped formalize:

- Rational agent models and performance measures

- Planning and search as action-selection mechanisms

- Learning-based control, where a learned policy plays the role of agent behavior

In many ways, Russell and Norvig provided the architectural grammar of artificial agents: the basic sentence structure of perception, internal state, decision, and action. Subsequent advances — from reinforcement learning to foundation-model-based agents — have dramatically expanded the representational and computational substrate on which that grammar is realized, but have not displaced the underlying architectural vocabulary they introduced. Even today, when we build LLM-based agents with planning, memory, and tool use, we are instantiating variants of these same foundational architectures.

This classical framing treats an agent as a decision-making unit interacting with an environment. A natural next step is to ask what changes when multiple such decision-making units coexist—each with partial information, limited control, and potentially competing objectives. That question is the starting point for multi-agent systems.

Multi-Agent Systems: Agents as Social Actors

The multi-agent systems (MAS) tradition emerged as a sub-discipline of artificial intelligence in the 1990s, drawing on distributed systems, game theory, and organizational theory to study coordination and interaction among autonomous computational entities.

In this literature, agents are commonly characterized by properties such as:

- Autonomy

- Reactivity

- Proactiveness

- Social ability

A frequently cited framing, due to Michael Wooldridge, is:

“An agent is a computer system situated in an environment and capable of autonomous action in order to meet its design objectives.”

Here, the defining emphasis is on autonomous action in decentralized settings. Whereas classical AI focused primarily on how a single agent selects actions, MAS research focused on what happens when multiple such agents coexist, interact, cooperate, or compete in a shared environment.

This tradition introduced and formalized:

- Agent communication languages and protocols

- Coordination and negotiation mechanisms

- Market- and auction-based interaction models

- Distributed problem solving

- Emergent collective behavior

Notably, MAS deliberately defines the concept of an individual agent without reference to other agents. An agent is specified as an autonomous actor situated in an environment; a multi-agent system is then defined as a system composed of multiple such agents. Social interaction is therefore treated as a system-level property, not part of the definition of the agent itself. This design choice keeps the agent abstraction modular: one can study single agents, multi-agent collectives, or transitions between the two without changing the underlying notion of an agent.

It is also worth noting that the MAS framing does not replace the classical AI notion of an agent, but re-weights its emphasis. Autonomy and decentralization are made explicit, while perception–action loops and rational decision-making remain implicit. The underlying abstraction is continuous; what changed were the research questions. Classical AI focused on how an agent chooses the right action. MAS focused on how collections of autonomous agents behave when no single agent has global control.

Together, classical AI and multi-agent systems give us a powerful computational picture of agency: agents as entities that select actions under objectives, sometimes in decentralized collectives. But this picture still tends to treat the environment as a stage on which decision-making plays out. A different lineage—rooted in robotics and cognitive science—argues that the environment is not merely a backdrop: it is constitutive of the agent’s behavior and, in an important sense, of its intelligence.

Robotics and Embodied Cognition: Agents as Embodied Systems

Robotics brings a different emphasis: the environment is not just “background” — it actively shapes intelligence.

Across embodied, situated, and enactive perspectives in cognitive science and robotics, intelligence is often framed as emerging from an ongoing perception–action loop: agents learn and adapt through sensorimotor interaction with their surroundings, rather than through abstract reasoning alone.⁴

This lens highlights that:

- Action is ongoing and time-coupled (even when we model it in discrete steps)

- Environments constrain and respond to behavior (“the world pushes back”)

- Perception and action are tightly coupled, often shaping each other over time

Even for purely digital LLM agents, the analogy is useful: tools, APIs, and live data streams can be seen as a kind of functional or “software” embodiment — interfaces through which an agent senses and acts in its operational environment.

Once we take seriously the idea that cognition is enacted through ongoing interaction, it becomes natural to ask what—if anything—counts as intention in such systems. This leads directly to cognitive science perspectives that foreground internal models, goals, and the attribution of agency: not just how an agent acts, but whether its behavior is meaningfully understood as being “for reasons.”

Cognitive Science: Agents as Intentional Systems

In many strands of cognitive science, agents are modeled as systems that can:

- Form and pursue intentions or goals

- Maintain internal state and (sometimes) internal representations of the world

- Select actions based on those internal states and representations

This centers the notion of intentionality: behavior that is meaningfully interpreted as being for reasons—in service of goals, plans, or preferences.

This perspective becomes especially relevant for AI when we ask:

- Does an AI system “intend” an outcome in a mechanistic sense (i.e., does it maintain goal states and plan toward them)?

- Or is “intention” primarily something observers attribute when a system’s behavior is coherent and goal-directed?

Agentics may need to accommodate both: the internal mechanistic story (how goals, state, and action selection are implemented) and the external interpretive story (how and when intentional agency is legitimately ascribed).

If cognitive science asks what it means for behavior to be intentional, economics often asks a more operational question: given preferences, information, and constraints, what choices should we expect? This shift from internal mechanism to observable decision-making provides a complementary lens on agency.

Economics and Game Theory: Agents as Decision-Makers

In economics, an agent is typically modeled as a decision-maker with preferences, information (or beliefs), and constraints. In game theory, that picture is extended to settings with multiple decision-makers, where each agent’s outcomes depend on the actions of others.

Agents are commonly abstracted to:

- Utility functions (preferences over outcomes)

- Information sets / beliefs (what the agent knows or assumes)

- Strategic interaction (how choices depend on others’ choices)

This perspective has strongly shaped:

- Market- and auction-based interaction models in multi-agent systems

- Mechanism design (designing rules so self-interested agents produce desired outcomes)

- Incentive- and game-theoretic thinking that is increasingly used in AI governance, safety, and alignment discussions

Notably, agents here are defined less by internal cognition and more by observable choices under constraints—a “revealed preference” style of modeling that often remains agnostic about what is happening inside the agent.

An important distinction in how Economics/game theory and Multi-agent systems (MAS) approach a plurality of agents: the former studies the logic of strategic choice under incentives and information in market and game-like settings, whereas the latter focuses on the computational mechanisms that let agents represent, communicate, coordinate, and act in distributed environments.

Economics models agents through preferences, information, and incentives. Sociology extends the picture by asking how those preferences and choices are shaped— and sometimes constrained—by roles, norms, and institutions.

Sociology and Organizational Theory: Agents in Roles and Institutions

Sociology and organizational theory add another layer to our understanding of agents. Unlike classical AI or economics, sociology does not offer a single canonical definition of “agent”; it focuses instead on how agency is exercised within social structures—roles, norms, institutions, and systems of authority.

From this perspective, action is:

- Enabled and constrained by rules and norms

- Shaped by roles, incentives, and authority structures

- Socially evaluated and governed through legitimacy, sanctions, and accountability

This lens becomes increasingly relevant as we place AI agents inside:

- Companies

- Workflows

- Institutional and governance processes

Many modern “agentic workflows” are, in effect, rediscovering familiar organizational patterns—delegation, escalation paths, specialization, approvals, and accountability—except that some of the “actors” are now software.

Sociology shows how agency is structured by roles, norms, and institutions—and how responsibility is allocated in practice. Philosophy pushes one level deeper by asking what it means to be responsible in principle: what counts as acting for reasons, and when an agent is an appropriate target of praise or blame.

Philosophy: Agents as Bearers of Responsibility

In philosophy—especially the philosophy of action—agents are often discussed in terms of intentional action: acting for reasons, forming intentions, and exercising control over what one does. This connects directly to questions of moral responsibility: when an agent is the right target of praise, blame, obligation, or liability.

This perspective matters when we ask:

- Who is responsible for an AI agent’s action?

- Under what conditions, if any, could responsibility meaningfully attach to artificial agents?

Even if we conclude that responsibility does not apply to AI in the human sense, the practical pressure to allocate responsibility—among designers, deployers, users, and institutions—will only grow.

If philosophy is concerned with responsibility in principle, HCI is concerned with responsibility in use. In mixed-initiative systems, agency is distributed across human and machine, making questions of control, trust, and intervention central.

Human–Computer Interaction: Agents as Collaborative Partners

Human–computer interaction reframes agents as systems that share control with humans, emphasizing collaboration rather than full autonomy.

This introduces ideas like:

- Mixed-initiative interaction

- Trust calibration (appropriate reliance)

- Legibility / transparency (being understandable and predictable to users)

A classic formulation describes mixed initiative as:

A flexible interaction strategy in which each agent (human or computer) contributes what it is best suited for at the most appropriate time.⁵

From this perspective, an agent’s practical agency depends not only on what it can do, but on whether humans can understand its behavior, anticipate its actions, appropriately rely on it, and effectively intervene or override it when needed.

Toward a Unifying View of Agents

Across these disciplines, “agent” rarely names a single, crisp object. Instead it points to a family resemblance: systems we treat as actors in the world.

A few recurring themes show up across traditions:

- Agents perceive and act

- Agents pursue goals or objectives

- Agents are situated in environments

- Agents may interact with other agents or humans

- Agents operate under constraints (resources, rules, norms, incentives, or physics)

We see that what differs is the emphasis:

- Classical AI foregrounds the perception–action loop and rational action selection.

- Multi-agent systems foreground decentralization and interaction among autonomous actors.

- Robotics and embodied/enactive perspectives foreground agent–environment coupling and the role of constraints in shaping behavior.

- Cognitive science foregrounds intentionality and the interpretation of action as being “for reasons.”

- Economics and game theory foreground choice under constraints, incentives, and strategic interaction.

- Sociology and organizational theory foreground roles, norms, institutions, and accountability structures.

- Philosophy foregrounds intentional action and the conditions for responsibility.

- HCI foregrounds shared control, legibility, and effective human–agent collaboration.

These are not competing definitions so much as different projections of a complex concept.

A Working Synthesis

A compact synthesis that respects these traditions is:

An agent is an entity capable of selecting and performing actions in pursuit of objectives, within an environment, under constraints.

This is intentionally broad – broad enough to include thermostats, trading bots, robot swarms, and interactive assistants – yet structured enough to support meaningful distinctions: degrees of agency, kinds of constraints, forms of interaction, and differing notions of “objective” (goal, utility, role obligation, or socially ascribed purpose).

Agentics, as a proposed discipline, would aim to provide a shared vocabulary for making these comparisons explicit – while sustaining the genuine differences each tradition cares about.

Looking Ahead

In the next post, we’ll turn to a set of related (and often conflated) questions:

Is intelligence the same as agency? Where does autonomy fit? And what do these distinctions imply for today’s “agentic AI” systems?

We’ll try and connect the cross-disciplinary concepts from this tour to current engineering practice—examining how contemporary frameworks draw boundaries between workflows and agents, and where older automation paradigms like RPA fit in the modern agent landscape.

Footnotes & Further Reading

- Russell, S., & Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 4th ed., Pearson, 2020. (The canonical AI textbook; Chapter 2 introduces the agent abstraction.)

- Wooldridge, M., & Jennings, N. “Intelligent Agents: Theory and Practice.” Knowledge Engineering Review, 1995.

- Wooldridge, M. An Introduction to MultiAgent Systems, Wiley, 2002.

- For accessible entry points into embodied/situated/enactive perspectives: Rodney Brooks, “Intelligence without Representation” (1991); Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson & Eleanor Rosch, The Embodied Mind (1991). For a robotics-oriented treatment of embodiment and “morphological computation,” see Rolf Pfeifer & Josh Bongard, How the Body Shapes the Way We Think (2006).

- Horvitz, E. “Principles of Mixed-Initiative User Interfaces.” CHI 1999.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply